Is it ever ok to use AI in a creative setting?

A poker-world fiasco with real-world creative implications

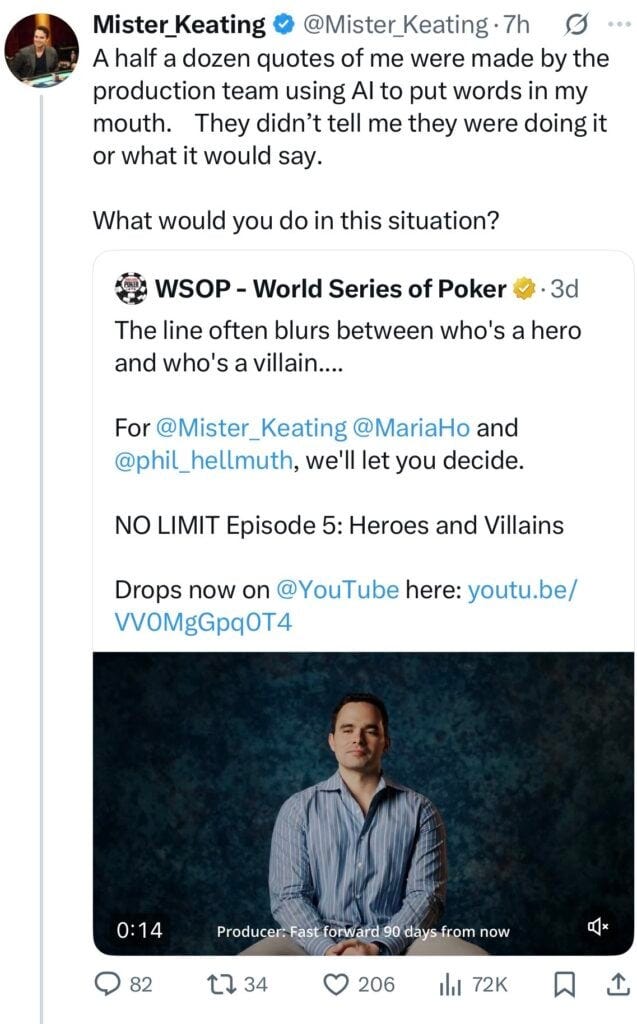

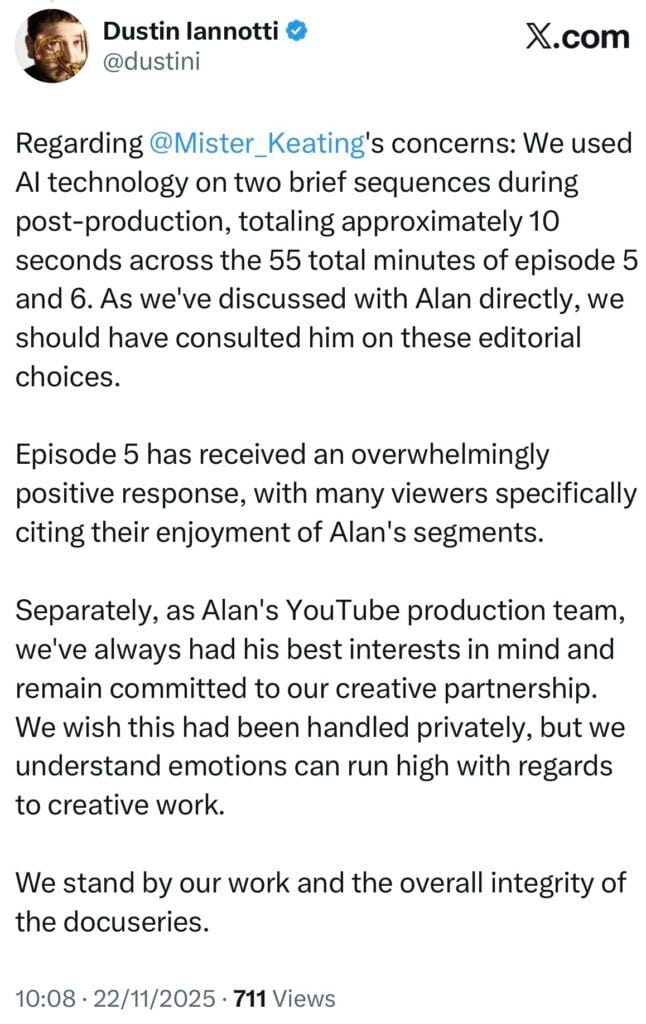

Last week, the poker world erupted over a scandal that, unlike most that cross my path on Poker Twitter, actually caught my attention.1 A few weeks back, a big-deal poker documentary, NO LIMIT, was released to much fanfare: over 650 hours of footage from the inaugural $25,000 Super Main Event at the World Series of Poker Paradise had been condensed into eight 30-minute episodes that promised to show the human drama behind the game of poker. Whether we will ever get to see all eight episodes remains unclear, since the first six have now been scrubbed from the Internet. As it turns out, the series creator, Dustin Iannotti,2 had seemingly not found enough usable material in the 650 hours that were taped and proceeded to generate lines for some of the series’ participants, including one of its stars, without their knowledge or consent.3

How did this come to light? Not because the series had a disclaimer that it used AI; not because the production company or any producers ever thought to say anything like, oh, by the way, we have used AI to enhance the storytelling; but because one of the players, Alan Keating, noticed something fishy about his own appearance and called the thing out on Twitter.

After the accusation, Iannotti admitted to literally putting words in players’ mouths—both Keating’s original call-out and Iannotti’s admission have since been deleted from the platform—but suggested that it wasn’t that big a deal. It wasn’t that many words, after all, and it helped the narrative.

Keating was not appeased. “This doesn’t deserve a reply and you know why,” he responded.

As someone who has appeared in dozens of documentaries, I was immediately on high alert. Whenever I sign appearance releases, I make certain that my words will not be edited in a way that changes their meaning. I scrutinize the language to make sure a narrative-happy producer can’t create a version of my interviews that differs from the one I actually put forward. I do my best to strike out any wording that allows for too liberal of an editing hand, requesting that any proposed substantive changes be approved by me. If the producers aren’t good with that, they aren’t allowed to use the footage. (I mean it, too. I spent a day taping with a major Canadian show last year, only to have to write off the time as a sunk cost after we couldn’t agree on language for the appearance release.)

And sure, despite it all, shit happens. You never really know how your words will be used. But the NO LIMIT situation, to me, seems to go squarely against the entire ethos of what a documentarian is striving to do. Contemporary documentaries document. They seek to capture the truth—and then present that truth in compelling fashion. This is not scripted or reality tv. Documentaries are a different beast. If you can’t craft a good story from hundreds upon hundreds of hours of footage and feel you need to resort to AI to help out? That seems a problem with the filmmaker, not with the material. It’s a sign of intellectual and creative laziness, pure and simple.

It’s also a sign of a decidedly skewed moral compass. Ethically, you have an obligation to be transparent about your work. Plan to use AI? Great. Wonderful. Go for it. Just tell people in advance and make sure they are cool with it. Some will be. Others won’t. Plan to present something as unvarnished documentary but make up dialogue that a living human never actually said? You’d better have gotten permission in advance to alter content “in keeping with speaker intent” or whatever legalese you want to use—and you’d better let the audience know that what they are watching isn’t just the human story you promised, but a story of humans enhanced with the help of AI.

As a writer, I’m allergic to the use of AI—whether secret or explicit—to replace the work of actual human creatives. But this has nothing to do with my own opinion. I think that if you want to use AI as a creator, you should absolutely feel free to do so—and I don’t think it’s useful to reject AI or go all Luddite about its implementation. AI is here to stay, whether I like it or not. But I also think that you, as a creator, have a responsibility to your audience and your subjects to be honest, to play by the rules that you’ve agreed to instead of secretly changing them partway through. That principle holds whether you’re a documentary filmmaker or a journalist or a screenwriter or anything else. I don’t think any of my readers—especially paid subscribers—would be happy if I suddenly told them that my pieces were partially AI-generated. (They are not. Not even a single word. Just for the record.) Journalists have lost jobs for far less.

Michael Shamberg, a longtime Hollywood movie producer whose credits include Pulp Fiction, Contagion, and Erin Brockovich, is at the other end of the spectrum from me when it comes to incorporating AI into creative work. Shamberg makes his own Generative AI videos and believes that AI will be as transformative to movies as were talkies. If there’s a pro-AI creative, he’s it. When I asked Shamberg for his thoughts on AI in documentaries, in general, and on this instance, in particular, he was quite clear: he’s very pro-AI, but within very specific boundaries. Want to add lines to a subject’s interviews? Ok, if it, “is done with the permission of the people with lines of dialogue in their mouths, and IF the viewer knows.” He went on to enumerate other possibilities—including how Ken Burns might use AI—but was very clear that, no matter what, there is one hard and fast rule: “the viewer should be told it’s AI.” And if the viewer is kept in the dark? “It is wrong,” Shamberg concludes.

With the ALL IN fiasco in particular, the issue goes beyond even using AI in secret, with zero disclosure or disclaimer to viewer and subject alike. An even more egregious failure is the attitude that it’s no big deal. That because the series is mostly not AI, we shouldn’t care that part of it is. Ten hours, ten minutes, ten seconds: it doesn’t matter. If the audience is not told that AI is in use, if you are misleading your public, it is a huge deal.

AI is upending the creative landscape. We can embrace it wholeheartedly or skeptically—we certainly can’t afford to ignore it; it’s “unstoppable,” as Shamberg puts it—but the crucial point is that we must embrace it ethically. And that means honesty, transparency, and the creation of a system of rules that preserves the integrity of the artforms we love.

*

EDIT: Nate and I are covering covered the scandal in greater detail (and from some different angles) on this last Wednesday’s Risky Business podcast. I will add a link to the episode is here when it comes out!

*

IMPORTANT ADDENDUM

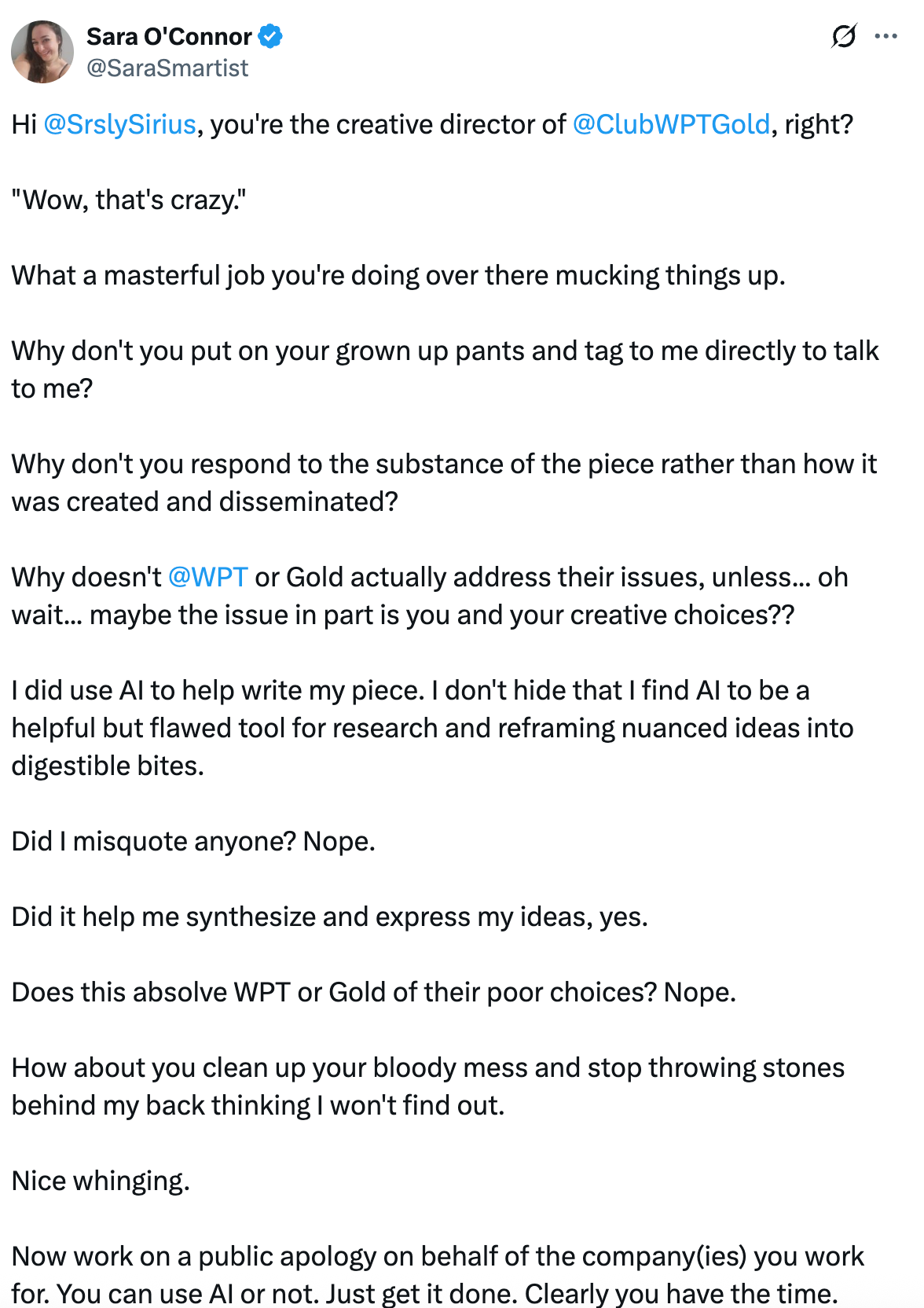

After I published this piece, I was made aware of yet another AI content drama in the poker world, this one regarding the use of Chat-GPT in writing an article for pokerlistings.com, here. After being called out for publishing AI-generated content, the author of the piece in question doubled down to say that, actually, it was natural and fine and all writers do this.4

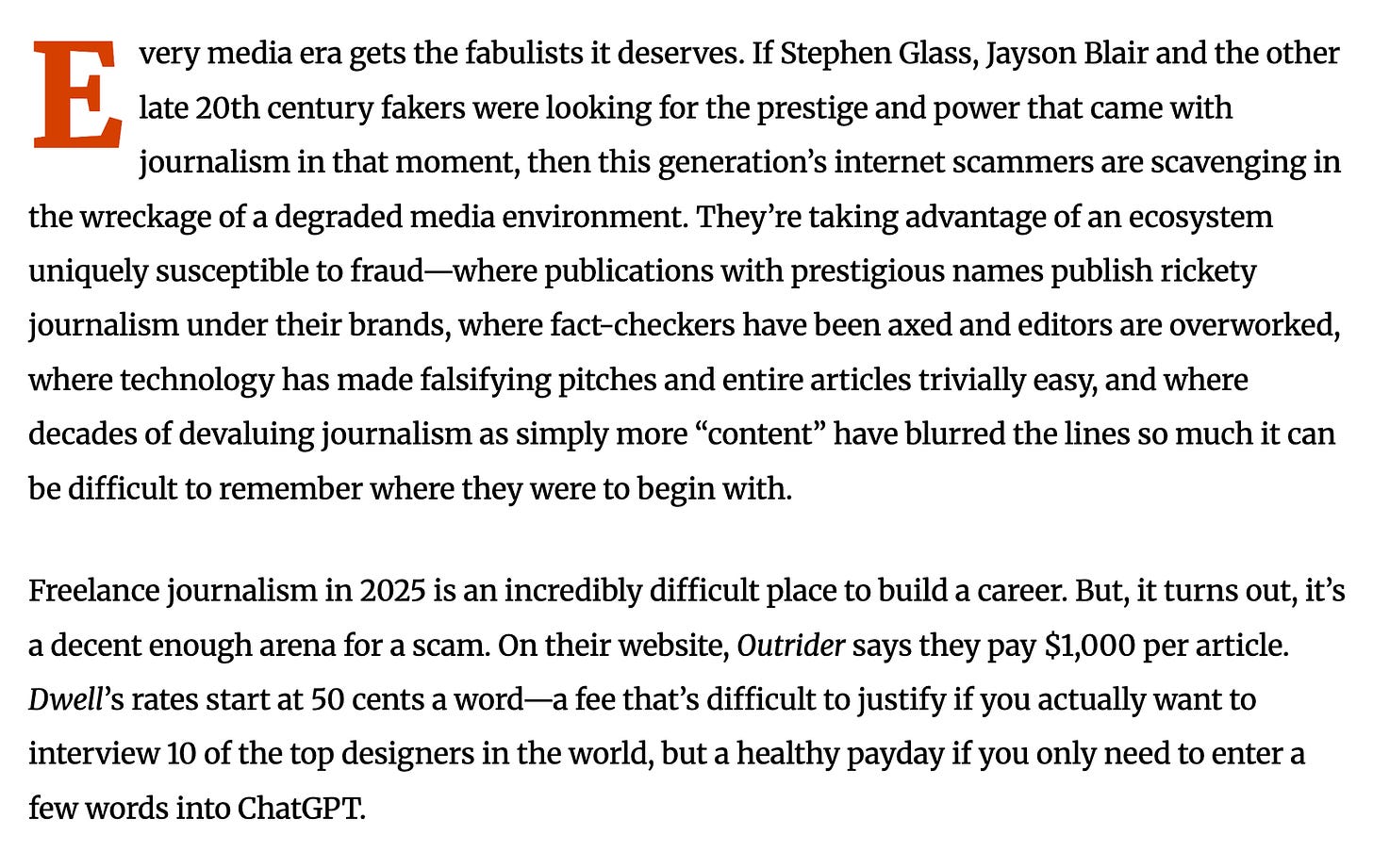

I am not trying to pile on the criticism, but I honestly cannot believe this has to be said: THIS IS NOT OK. No, you cannot use AI-generated writing in your pieces. No, all journalists are not doing it. No, it is absolutely not common practice. And yes, you will have your pieces removed and your assignments revoked if you try to pull this off in any self-respecting media publication. If a publication fails to notice the use of AI and publishes a piece that relied on it—something which is happening far too often—it will then retract it in full and typically issue an editorial apology.

There happens to be a wonderful—non-AI!—piece of reporting on the phenomenon from just last week, at The Local. I highly recommend reading the full piece, but here’s an excerpt.

There’s a word for journalism that was actually written by ChatGPT, and Nicholas Hune-Brown isn’t afraid to use it. It’s called a scam.

Iannotti is the founder and CEO of Artisans on Fire, a Vegas-based video production studio with 18 years of experience, according to their website.

After Alan Keating, Alex Keating (no relation) also came forward with allegations that his contribution was altered with AI. As of this writing, no other players have.

Sara reached out to me to ask that I clarify that she didn’t use those exact words. She absolutely didn’t — that’s why they are not in quotation marks. This is my impression of her stance based on multiple tweets that she sent to various people defending her actions (some of which seem to have been deleted).

Hey Leapin’ Maria,

Geezer prof here wringing hands over AI’s threat to original thinking. At the same time a fan of the possibilities.

This tension will ripen and it appears we aren’t ready ethically, or more importantly, equipped to keep it safe.

Great article.

A few observations:

1) So the two people whose lines were altered by AI are people named AI__ Keating? Like the first two characters of their name look like the letters "AI" and their last name is basically "Cheating?" Are we sure this isn't a publicity stunt?

2) What makes a commercial video about a poker tournament a "documentary" and not reality TV, or for that matter an advertisement? Especially if it seems like it's being produced by the PR teams of the players featured?

3) I think one of your shoes is on backwards as you're ascending to heaven.